Knowledge Rich – what should schools actually teach their pupils?

Here at PTE we believe that a knowledge-rich curriculum (KRC) is an essential part of any great education.

In recent years, much has been written on what a KRC actually is and how one should be developed. There are many different views on this, but what they all have in common is the belief that it is what children are taught that really matters, and everything else – pedagogy, assessment, qualifications, etc – serves that, not the other way around.

With this as the starting point, one then has to make some really important, but really hard, decisions about what gets onto the curriculum – and also what has to be left out. After all, kids have only finite time at school & limited working memory, so we need to think carefully about what things are most important and why – in each subject and across the curriculum as a whole.

It’s at this point that we often revert to generic statements such as “the best that’s been thought and said” – but what does that mean in practice? We also have to consider the “opportunity cost” to every decision made too – if we use up the time available to include X and Y, what can we not include as a result?

This is where it gets tricky – and where the really interesting part of the debate is to be had, even amongst those of us who are committed to the knowledge-rich approach. Why? Well, WHAT we consider to be important for pupils is inevitably going to be informed by our views on WHY we educate kids.

On this there is rarely full agreement, even between close colleagues who work together every day. Given that we don’t have agreement in the staff room, it’s no surprise that we don’t have agreement on this across society as a whole. And you know what? That’s okay.

Indeed, it can even be argued that having different views on what should be taught and what has to be left out is essential. If all schools taught exactly the same stuff, then that which wasn’t taught could be lost to society forever. So having different things taught by different places means more of what mankind has learned to date can be passed down to the next generation.

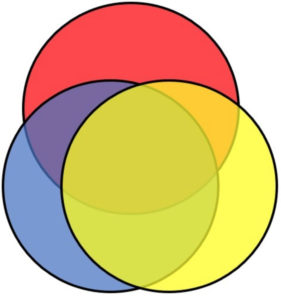

That said, within subjects one would still expect a common core to be seen across most schools – so we can picture different curriculums as being a bit like venn diagrams, where they all overlap with one another, but also have parts that are unique to themselves too.

Whilst there are probably as many takes on how to decide what to include as there are people, a few general approaches do dominate. Some argue that education should teach children to be activists in the world, and to prepare them to challenge injustices and inequalities – and that what is taught should inform this aim.

Others would argue that children should be taught things that are “relevant” to their lives and communities. And others argue the opposite – that the kind of things children would otherwise never come across should be prioritised to broaden their horizons beyond their current life and community.

Others still would put the main emphasis on preparing kids for the world of work.

Within the knowledge-rich “community” though, there are generally two main schools of thought around what kind of knowledge should be prioritised.

One approach is to cover things that enable pupils to engage with and take part in the conversations that shape society. Some call this “cultural capital” or “cultural literacy”. This is the kind of thing advocated by E.D. Hirsch and it was the thinking that drove him to write “Cultural Literacy” and come up with his “list” of the things that he felt every American needed to know. It’s also the thinking that underpins much of his work since then, including “Why Knowledge Matters”.

The other approach is that pushed by Michael Young – “powerful knowledge”. Having been opposed to a knowledge-rich approach earlier in his career, in “Bringing Knowledge Back In” he argued for such a curriculum for children. However, his take is subtly but importantly different to Hirsch’s, in that he believes cultural literacy is too limited in its take on things. In contrast he thinks “powerful knowledge” enables learners to go beyond that which is already known – more of his thinking can be read here.

Whichever your own view on these approaches, they provide a framework for dealing with the question of what to include and what to leave out. And this is key for everyone involved with designing or teaching a curriculum. After all, if you don’t know what you’re trying to achieve, you probably won’t achieve much very well.

There is another risk that schools face in this regard. Lots of people who don’t teach children have very strong views about what children should be taught – even if they have no experience or expertise in education, beyond their own school days.

Politicians, government departments, quangos, charities, faith groups, professional associations, interest groups, and (of course) celebrities – it can sometimes feel that there is no shortage to the number of organisations and individuals with suggestions as to what it is that schools should teach.

As a result, if teachers don’t have a firm and informed view on what is important others will fill the vacuum with their own priorities and prejudices. During 2018 PTE collated as many “schools should teach” suggestions as we could find with a simple Google search. Among these were sarcasm, toothbrushing, first aid, various sexual activities, how to get pregnant, and how to not get pregnant.

In total we spotted 213, which is more than one for every day of the academic year. And it’s not as though teachers are sat around twiddling their thumbs, trying to find things to do with their pupils to fill the time…

What should schools teach their pupils, then? Well, we think that’s for their expert teachers to decide, based on their subject expertise. It should come from a place that thinks that what is taught really matters, and recognises that how this manifests itself will differ from place to place – depending on people, context, and values.

The key is for teachers and parents – current and prospective – to ask schools what informs their decisions, so they can understand and act on the answers given. If a school has carefully considered these issues, and can explain it coherently to you, then one can be reasonably confident that their curriculum starts from a good place.