Developing a Knowledge-Rich Art Curriculum Part 1: The ‘Why?’

David Morel, Head at Willingham Primary School, gave a talk with his colleague Sara Varty at our Wonder Years conference on knowledge-led art curricula. Here, he writes down some of his thoughts on the topic for our blog. You can also see the PowerPoint he used on the day here.

One of the key arguments that people throw at a Knowledge Rich Curriculum is the notion that teaching knowledge directly will stifle creativity. Despite signing up to this viewpoint earlier in my teaching career, I now believe that this is a misguided precept that indicates a misunderstanding of how the brain works and what creativity/problem solving/abstract thinking is. I was fortunate enough to talk on this alongside the Art teacher from our school the PTE Wonder Years conference on 26th January, where we outlined our view on what constitutes a brilliant art curriculum.

In the first of this two-part blog, I will lay out the counter to this ‘creativity’ argument, giving the ‘why?’, before my colleague lays out the ‘how?’ in the second part, and gives practical actions and concrete examples of how to implement curricular development in art.

The Lego Analogy:

Imagine a child in a room with no Lego bricks being asked to create an inspiring model of a building. You can’t create from nothing and this is, perhaps, a metaphor for a ‘creative’ curriculum, where key learning goals are skills that in reality cannot be taught. Creativity is domain specific and not a skill that can be generically taught.

Or, imagine the child in a similar room, but this time with piles of disorganised bricks and no prior experience of how to fit them together. Ask the child to build something amazing and they will struggle – cognitive overload will ensue and focus, attention and effort will drop. Within this ‘discovery’ curriculum they may build something (at least they’ve got some bricks), but I’d wager that for most, the progress will be slow and random.

Now imagine the child in a third room with a Lego pack. The good people/subject experts at ‘Lego Towers’ have selected something worthy to build, identified all the bricks that are needed and provided a step by step guide on how to put the model together. So long as the child follows the steps, they will succeed in producing a worthy model. Ok, so the outcome was determined by someone else and they have been heavily guided through the process, but they have achieved success. Now imagine this happening again and again. The child will be shown how different bricks fit together in different ways and will build a bank of memories of models that they have successfully built. With enough mental models and enough bricks, when asked to ‘create’ something new, they will have a wealth of information in their Long-Term Memory to allow their Working Memory to really get creative.

If the bricks are knowledge and the models are schema in LTM, this child, I would argue, is the one who will be most ‘creative’ when confronted with the request to build something new, not the child in room 1 or room 2.

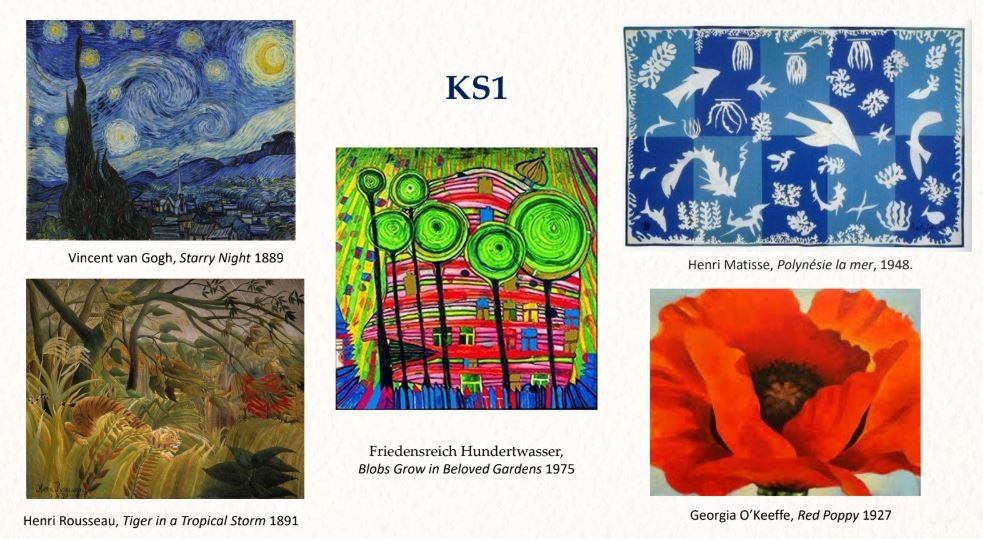

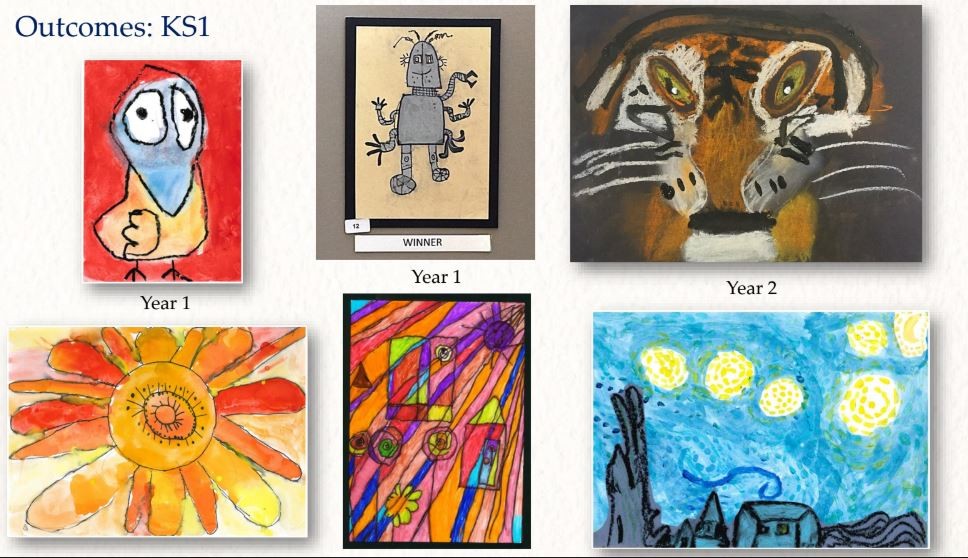

Although not a perfect metaphor – and with an acceptance that some human minds sit ‘outside the bell curve’ and are creative genius’ – this helps to explain how we teach art at Willingham Primary School. We select the best art from the worthiest artists and teach the children not only about the piece itself, but also about the wider historical context at the time the artwork was created. The artistic techniques are carefully identified and practised by the pupils – building to automaticity, both the muscle memory and disciplinary knowledge that pupils need, over time. The pupils practise these techniques and produce a piece of work that will closely replicate the original – they achieve success, as the steps are laid out clearly and practised rigorously.

As well as my shifting views on the reality of creativity, what I’ve seen in the outcomes of our curriculum have led me to the view that Growth Mindset is domain specific and a condition to be created, again not a thing to be taught. Because of our curriculum, our pupils’ long-term memories are full of successes; when confronted with a problem in art, their memory says ‘I usually succeed, so I’ll try again’. I could not say that this is the case within all domains in the school. Our children have great growth mindset and resilience in art, but it’s never been ‘taught’: it’s a condition that’s been created.

And what about the outcomes? Well, the pupils create incredible pieces of work that we display widely around the school and on our art blog. But so much more beyond this, they are supported in becoming inspired and inspiring people, the kind that you’d want to go to an art gallery with. An anecdote that highlights this is from a Year 2 child in the National Gallery last summer.

Child: I think that painting is a Rousseau.

Parent: Oh, have you seen that painting before?

Child: No, but it’s in a jungle and Rousseau liked painting jungles, and the colours and trees look similar to the one with the tiger in, Surprise! I think it was called.

Parent: Oh.

Now, to me it doesn’t matter whether the painting was indeed, a Rousseau or not, the child had engaged with a painting in a way that many adults would not have been able to do and got more from her trip to the gallery than many 6 year old would………and of course, when they went to read the information, she was correct in her assertion………… and she’d painted a beautiful picture of a tiger that is displayed along with other ‘masterpieces’ in the corridor of our school.

For most, knowledge is the source of creativity, not an inhibitor – you can’t create from nothing.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of PTE or its employees.