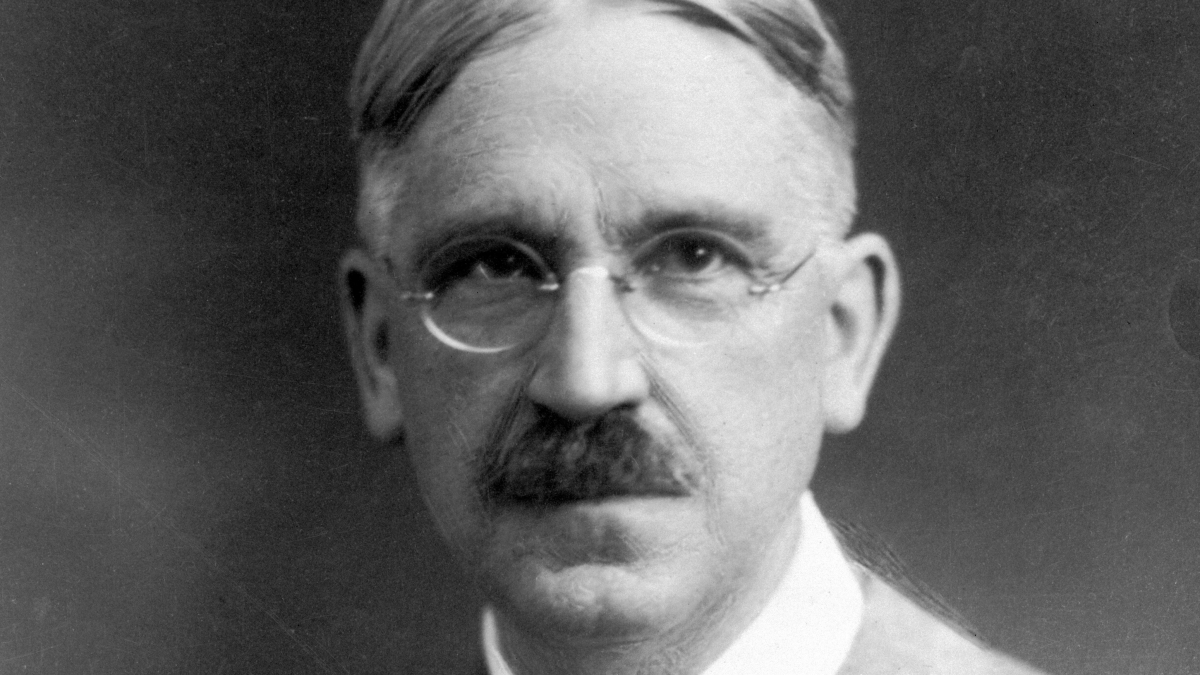

Great Education Thinkers: John Dewey

“The native and unspoiled attitude of childhood, marked by ardent curiosity, fertile imagination, and love of experimental inquiry, is near, very near, to the attitude of the scientific mind” – John Dewey

It may come as a surprise that John Dewey is included in our feature on great education thinkers. After all many of our colleagues would argue that his theories are misguided and that his influence has been almost wholly negative. However if the only great thinkers were those who had accurate theories there would be very few great thinkers. And secondly while we agree that his influence has been in part pernicious it is also true that no single philosopher has had as large an influence on teachers. There is always a danger in any argument to create a strawman out of your opponents position, we often hear that progressive education involves no real curriculum, no discipline and is based on a wildly utopian vision. This may be close to what is argued for by some practitioners but is this true to the Deweyan outlook? By investigating one of the most intellectually serious progressive educators we can give progressive education a fair trial and take on points from a different perspective. Further seeing the key differences between our approach and Dewey’s can help put our core commitments into focus.

With the defence of our enterprise out of the way we can examine Dewey’s thought. Dewey can be difficult to read and at times quite confusing. Often when using ordinary terms he has in mind technical notions that differ from their everyday use. This may be a factor in why his work has been interpreted in a variety of ways, particularly by practitioners who have used his work as a springboard to implement radical progressive programs. Dewey himself founded a school and wrote widely on a number of philosophical issues beyond education. While we can only cover a small portion of his output we will focus on a few of his most famous texts as well as his practices to try to get a real sense of what he advocates.

First it is worth being clearer on Dewey’s background philosophical commitments since they influence his thoughts on education. Dewey is often labelled a pragmatist philosopher, broadly speaking pragmatists take the usefulness of a theory to be the most important feature. The key to understanding Dewey is through his conception of ‘experience’, for him experience is not simply perceptual experience such as seeing or hearing. What he means by experience is much a wider notion with a distinctly experimental quality, we bring to it an interpretive framework and consciously relate to and learn from experience. Dewey viewed the scientific method as paramount to practical problem solving and analogous to what is found naturally through experience. For him all inquiry is linked to discovering and ultimately improving the way things are in a social setting.

Democracy was also of the highest importance for Dewey. For him democracy means more than the chance to vote for a candidate to represent you in parliament. Democracy is the ideal form of society whereby communities decide on how to solve the problems they face through deliberation. The key to achieving a functioning version of this ideal is education. Without the proper education citizens would neither have the knowledge nor the skills to take part in productive deliberation. This form of democracy for Dewey promotes the maximum amount of freedom for humans and is ideal for their growth.

To truly get to grips with Dewey’s theories we would need spend lots more time than we have presently on these philosophical notions. A picture should however be growing that will stem into his educational theory, that is how we learn from natural circumstances is the key to how we should organise our schools. Every experience in and out of the classroom is an opportunity to grow depending on both what constitutes it and how we approach it. Rather than being unique school should be viewed as a directed continuation of this process which is inherently educative.

Progressive Education

The role of the teacher is to create an environment in which the students can have experiences that they learn from. As a child grows, particularly in the earliest years of development, their capacities and abilities to interact with the world grow exponentially. Dewey thought that the teacher should help to continue this progress, in a sense mirroring the work of nature.

What Dewey advocates is familiar by now, his most radical suggestions concern curriculum and behaviour. Instead of a subject based curriculum he thinks that students should start with material that directly relates to their own experience. The teacher should help students by finding relevant sources for them to continue studying their interests. A Deweyan curriculum might involve information from any subject but would be based around solving some problem that the students had formulated. The key here is motivation, students are much more likely to engage and learn from material if it comes out of their own interests. This again mirrors how we learn in nature, we begin acting out of impulse or desire but have to take on board information from our surroundings if we are to succeed. If we are apathetic we will not pursue action and will not learn.

Traditional education on the other hand is deemed to create an artificial environment without stimulating the interests of the students. This means that it fails to create an educative experience. While it may work for a few, Dewey argues that for many the content of the old curriculum is antiquated and of little use. Dewey explicitly states that the content of the curriculum has no ‘abstract value’ and should be regarded only in so far as it promotes growth and can be useful to us in the present.

A popular line of criticism is that Dewey’s approach will limit students access to the world by focusing on their own experience. The thought here is that students from more deprived backgrounds will be confined in their educative experience if they are never exposed to their cultural heritage. However we need to bear in mind that experience is a wide notion. Therefore all the things that have shaped our society have a role to play in the curriculum. A Deweyan approach would not do away with history in favour of popular culture as is so commonly argued by progressive educators today. For example the Roman’s political institutions and customs have been hugely influential on our society, a student would have to engage with them to fully understand his own experience. An interest in our society then would entail some ancient history being on the curriculum. This does mean that history would only be approached in so far as it is useful for understanding the present which is somewhat different from current approaches.

Upon this interpretation science looks as if it would become the primary focus of the school curriculum. Science and technology have had such a large impact on our society that they are a ubiquitous part of our lives and therefore a prime candidate for making up a large part of a progressive curriculum.

A further criticism of progressive education has been that it is child centred and the teacher has no role as an authority. Dewey clearly views the teacher as something closer to a guide than is the case in traditional education but this does not mean that the teachers role is merely as an onlooker or her expertise are not valued. Alongside creating the curriculum they can use pieces of their much wider experience to help develop the students thought. After the initial impetus is provided by the student’s interest the teacher shapes the direction the student travels by choosing curriculum materials.

The overall picture is very different from our usual concept of schooling. We couldn’t say what we expect students to leave school knowing or being able to do. Instead the idea is that they are put in the best circumstances to learn and the results follow from this. It is worth stressing again that this in line with Dewey’s commitments to naturalism and scientific method. We don’t know the results of an experiment before we have undertaken it neither do we know what we will learn in our everyday lives prior to actually learning. In this sense education is a continuation of nature and is an ongoing process.

Behaviour

Dewey thought that the majority of negative classroom behaviour was caused by the failings of traditional schooling. Thanks to both the restrictions placed on children via class arrangements and curriculum students are likely to lose motivation leading to poor behaviour. Advocating punishment and discipline is only seen as furthering unnatural restrictions on students. Exclusions and discipline could be used as a last resort if a student is disrupting others but these are exceptional cases and not the norms on which to base our systems of behaviour management.

Compared to Dewey’s curriculum vision these suggestions seem much weaker and formed on sentiment rather than evidence however he would argue that they fit the same picture. A truly educative experience is not one that is constrained and must be motivated by real interest rather than through being coerced.

Given that an element of discipline and teacher authority appear to be the only ways to encourage good behaviour particularly in the more disadvantaged schools one of two things must be true. Either schools that have attempted a progressive education have failed at providing a truly stimulating environment where students are motivated and do not feel restricted. Or secondly Dewey is wrong about behaviour and the most effective way to manage it is with a stricter approach. While many will suspect the latter to be the truth if it is not it just points to the extreme difficulty of running a school in a progressive manner, a problem which we will come to next.

An evaluation of Dewey’s approach

His naturalistic approach draws our attention to two important things. Firstly that motivation is key and secondly that we cannot totally control outcomes. The first point is perhaps the best thing about progressive education, it recognises that so much of why students succeed and fail is due to motivation. If the student really has no interest in a subject and never gains one then teaching them is an uphill battle. The role of the teacher must be to try to encourage interest and fascination in the material they teach. The second point is that we only truly control how a student learns and not every outcome. It is tempting to view a job well done as a student being able to recall information on a test but we also have to ask what did they internalise and whether it helped them grow further interests. Even when devising knowledge based curriculums this is something we must always bear in mind.

Problems and objections

No one will be surprised to hear that we reject Dewey’s educational outlook. It is however important to recognise why. We will distinguish two different sorts of responses to Dewey. One is a practical worry with how viable his methods are and the second is more theoretical looking at his values.

The first set of worries is practical, we have already hinted at this problem when thinking about his suggestions on behaviour management. Beyond behaviour there is the question of how it would be possible to implement his theories more generally. In an ideal world each student could follow their own interests and experiences with teachers who each have expertise in science, maths, world literature, history and economics. However the reality is that there are few genuine polymaths and each individual child is liable to have different interests. Creating a system that could run effectively following this model would require radical changes to structure and teacher trainings. The difficulty of creating a flexible curriculum is one that is recognised by Dewey, he sees it as a challenge however there is reason to think that it is an impossible dream.

Another issue is with his concept of interest, although we highlighted the positive side of making sure students are motivated he takes this point too far. In order to gain interests it is often the case that one needs relevant background knowledge and exposure to context. Without any context it is difficult to encourage interest in learning about many periods of history or many of the great works of the past. Take your pick from any of the greatest writers and this point is apparent. For instance Tolstoy may seem disconnected from our experience and without having any appreciation of the modern novel may simply be baulked at due to length. Clearly Dewey thinks that it’s the teachers job to widen experience so that it includes a larger collection of material but who is to say that starting at initial interest will ever lead to the great authors of the past. Interest is important but it may not always be the correct starting point, at least one function of the educator is to help students gain access to culture. Putting this criticism another way just because someone is not interested in something does not mean these things are not interesting, it just means that the students are not in a position to appreciate them prior to understanding context.

This point leads us on to our second set of worries that are theoretical, it seems that Dewey’s picture is overly utilitarian as it views no part of the curriculum as intrinsically valuable. We have argued at length that some knowledge is of intrinsic value to students. Dewey’s picture runs the danger of having too narrow a curriculum and not encouraging students to learn about the parts of our culture that our interesting without having obvious practical value.

Another large issue with his theory is the desire to jettison traditional subjects. There are a number of problems with this for instance it could potentially limit progress in a number of domains since division of labour is required given the amount of different areas that exist. Also as we have covered in previous blog entries there are subject specific thinking skills and it is not clear on a Deweyan picture how these would be retained if problems are approached from a more general outlook.

Conclusion

Although Dewey fails to motivate his radical suggestions we hope that this quick survey has shown that his views are not the same as the ones suggested by many progressive educators. He does not advocate teaching without a curriculum or only focusing on modern culture. What is particularly interesting in his approach is starting from the question of what makes an experience educative. While we have tried to focus on the positive aspects of his theory he also devotes a lot of time providing criticisms of traditional education, these we will have to leave for another time.

On a wider note we think that everyone should read and take seriously Dewey’s positions regardless of political or educational views. If anything todays polarisation of views is something that a Deweyan model of inquiry would look to combat by considering a diverse set of views, looking at the evidence and trying to come to an outcome through engagement and not belittlement. Whether this is a good model for schooling or not remains questionable but in terms of debate it can only help to move us forward.

Reading list

1916b, Democracy and Education – John Dewey

1938b, Experience and Education – John Dewey