Exclusions Make Our Schools More Inclusive

Our Director Mark Lehain has written this blog:

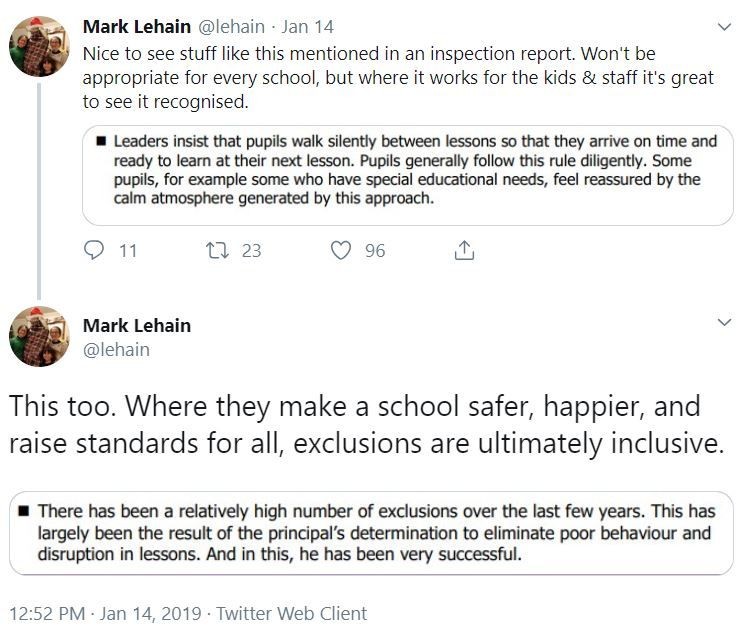

Yesterday I had my attention drawn to a newly-released Ofsted inspection report. It was glowing about the school in question, and a couple of bits caught my eye as they were so unusual, so I fired up Twitter and posted this:

I’ve written elsewhere about the confusing and contradictory messages given by authorities about exclusions. One day you might see a letter from a regional director saying exclusions are too high in their patch, and the next read an inspection report praising a school in that area for its turnaround (and the school in question have a very high exclusions rate indeed.)

And while you’ll never see a politician explicitly say that they will reduce Heads’ abilities to run their schools as they see fit, they will hint at terrible consequences if schools don’t do things, or allow their officials to say, in MAT reviews and the like, that exclusion rates are too high and must come down…

Regardless of what others say I’m of the belief that having the power to exclude a child is an essential one for those we entrust to run our schools. I am also of the view that we cannot have a truly inclusive education system without exclusions.

I say this for two important reasons:

- effective use of exclusions improves the standard of behaviour in general – to the benefit of all, but our more vulnerable students the most; and

- exclusions can be the wake-up call needed for children and their families to take poor behaviour seriously and change things for the better.

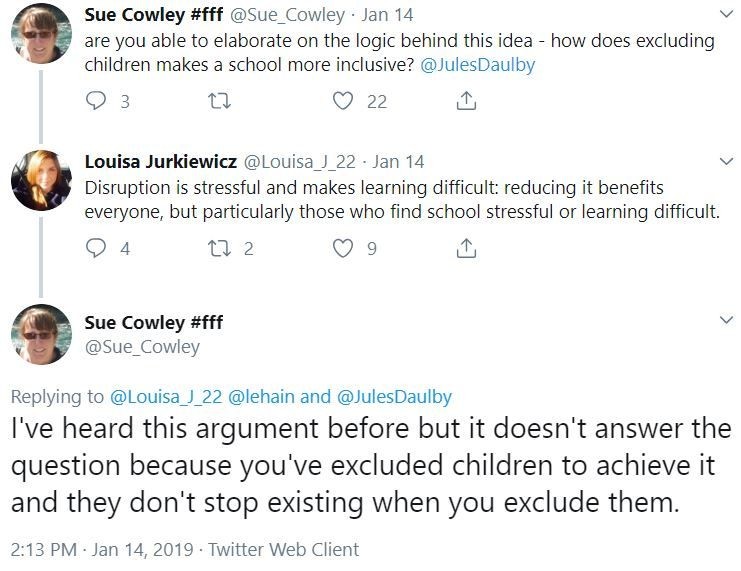

My logic for the first point is quite simple: for a school system to be truly inclusive, those who work and study there must first and foremost feel safe. No school can be safe without effective behaviour systems, and no behaviour system works without an ultimate end point beyond which no one can go without consequence. By having such an end point and improving the general behaviour, we actually reduce the number of children who reach and exceed it, ultimately keeping more children in school, and being more inclusive as a result.

As usual, on the topic of creating great school behaviour cultures, Tom Bennett has said it best:

“Exclusions are needed as a last resort, or the entire system before it chokes. If there is no terminus for extreme persistent misbehaviour, then anything is permitted up to that point too. Exclusions therefore aren’t a necessary evil. If they are necessary, then they are not evil.”

Some will agree that exclusions can benefit those who are still in school and experiencing fewer disruptions and so on, but rightly ask about the children who are excluded.

The thing is, exclusions CAN be a wake-up call: I’ve seen it so many times as a teacher and a Head. Sometimes, in spite of everything else a school or family does to support a child, it takes a really serious sanction like a fixed-term, or even permanent, exclusion to trigger a positive change.

It is only when a child is ready to look at the consequences of their bad behaviour and commit to improve it that they have a decent chance of being genuinely included in the truest sense of the word: welcomed by peers, supported by teachers, and able to get stuck into their learning properly. Ideally this wouldn’t require an exclusion, but sometimes it does. Preferably they can manage their turnaround at the school they’re already at, but sometimes it might need to be a fresh-start at another place – be that a great school or PRU.

Overall then, judiciously used, exclusions do make our school system more inclusive overall. Let’s not kid ourselves artificially avoiding exclusions will bring about better inclusion by any meaningful definition. And let’s not maintain that exclusions are the end of a child’s chances in education –there are too many examples of it leading to the successful re-inclusion of children one way or another.