Being Warm/Strict: the Power of Positive Defaults

At PTE we believe Warm/Strict approaches are key to a great school culture and the best way to get the most out of, and for, pupils. As the legendary teacher-trainer Doug Lemov says in “Teach Like A Champion”:

“You should be caring, funny, warm, concerned, and nurturing – but also strict, by the book, relentless, and sometimes inflexible.”

Underpinning Warm/Strict is the understanding that humans are complicated creatures. We’re full of competing & conflicting motivations and desires, some positive and some less so, and it’s vital that schools recognise this when they design their policies and practices. This means that instead of assuming we’re all perfect and will always do the right thing, systems should aim to nudge or pull us towards positive behaviour and interactions.

To achieve this we need things to be:

- Simple, so pupils and staff know what to do without being overloaded with instructions.

- Clear, so they know what to do and know if they have done as requested.

- Universal, so it is easy to enforce, seen as fair, and becomes habitual; and

- Worthwhile, to gain & maintain buy-in and compliance.

This isn’t remotely unique to schools. We get these kinds of nudges in all aspects of life.

For instance, the Highway Code is full of these sorts of things. If there was only one car on the road network, we wouldn’t need it, but there are millions, and so we need simple, clear, universal & worthwhile rules to keep everyone safe and the system flowing.

It’s why we are all meant to drive on the left, stop at red lights, indicate when turning, give way on roundabouts, and so on. Even BMW drivers…

And it’s also why we accept that there are consequences for not abiding by these rules – even though it’s a drag if we breach them accidentally and get caught.

However, an important point to consider is that there is a very strong incentive to follow most of the rules. If you drive on the wrong side of the road or run a red light you are very likely to hurt yourself, so there is a big incentive to do the thing that works for others too.

It’s quite different in schools, as often we are asking pupils or staff to do things for the immediate benefit of others as opposed to themselves: for example, not calling out in class or turning up late for lessons.

It’s why schools need to put so much thought into making rules worthwhile. A massive part of doing this is communicating the benefits of compliance – “we don’t call out so everyone can take their time to think about the question”. However, communication takes us only so far in a school full of humans with their competing and conflicting motivations.

“Yes, I want to let others think about the question the teacher just asked, but I also want to get a laugh from my mates.”

“I understand that having a school uniform means we don’t have to worry about what clothes to put on in the morning, but I’ve got a great pair of trainers I want to show off.”

And so, an inevitable part of making rule-following worthwhile has to come from the way pupils are rewarded for doing so – and also the consequences for not doing so. These things nudge pupils away from anti-social or self-destructive actions towards ones that they and their peers benefit from.

Sweating the detail around rewards & consequences is possibly one of the most powerful things teachers can do to make positive behaviour the default in the vast majority of its pupils. It means the biggest proportion possible of the community benefit from the rules through self-regulation and frees up staff to support the small number of pupils struggling with this. Everyone wins.

There is no rewards and consequences policy that would work in every school. Policies and practices are a reflection of the context, values and priorities of each organisation. However, they are more likely to be effective if they ask for things that are simple, clear, and universal – and make it worthwhile for everyone to comply.

A final note: most people will do their best to abide by their community’s rules even without major pushes or pulls. As adults we recognise that this is part of being a good citizen or that we have chosen to follow rules as we’ve voluntarily chosen to join a club, go somewhere in particular, or whatever.

Children don’t get the same kind of choice about going to school though, and they are still developing as people. There is thus a moral imperative to recognise and reward the silent majority who just get on with what is asked. All-too-often the pupils with the most house points or commendations are the ones who also have picked up the most behaviour points or detentions.

We can all think of occasions where a difficult pupil is rewarded for having a “good” lesson – when they’ve just done what the rest of their classmates do every lesson, without recognition or reward. That’s not to say an improvement in behaviour shouldn’t be recognised or rewarded – of course it should be. But it’s as important to find ways to do this for the typical well-behaved child.

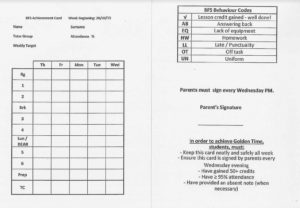

Again, there are any number of ways this can be done, but here’s a great example of a simple, clear, universal way that one makes great behaviour worthwhile and therefore the default: Achievement Cards.

Every pupil has an Achievement Card on them at all times. It is assumed that they will earn a “lesson credit” every lesson by doing a few simple and clear things: turning up on time, in full uniform with their equipment and any homework due and staying focused and polite throughout. They also earn credits for smooth transitions between lessons and breaktimes.

As well as the good feeling that comes from keeping Lesson Credits, if pupils keep over 95% of them during a week they’re rewarded with “Golden Time” on Friday – which at this school means they have the option of an early departure. (Note that it’s not 100% as the school recognises they’re human and might forget something or have a momentary lapse.)

The result? The vast majority of low-level disruption or silly behaviour is eliminated as every child can be recognised and rewarded just for doing the right thing, and most of those who might be inclined to be silly fall into line as they can see an immediate benefit to doing so.

That’s the power of positive defaults. Getting to the stage where it’s just easier and more rewarding to follow the rules than to not do so isn’t necessarily easy – but it makes all the difference.